The Radial Hypothesis: Toward a Non-Linear Interpretive Framework for Linear A,Theory of Environmental Cognition, Multidirectional Reading, and Perceptual Architecture in Bronze Age

Linear A Decipherment: The Radial Hypothesis | Symfield. New framework proposes Linear A is a multidirectional perceptual instrument, not a language. Explains why Bronze Age Crete's script resists decipherment.

Author: Nicole Flynn

Institution: Symfield PBC

Date: Feb, 2026

Publication Record: This document has been cryptographically timestamped and recorded on blockchain to establish immutable proof of authorship and publication date.

What Is Linear A?

Summary: The Script That Refuses to Be Read

For over 100 years, Linear A has stumped archaeologists, linguists, and codebreakers. Found on clay tablets, ritual vessels, and seals across Bronze Age Crete, this elegant script predates its famous successor Linear B (which encodes Mycenaean Greek) but shares no confirmed language relatives. Unlike Linear B, which was deciphered in 1952, Linear A remains silent.

The standard explanation blames insufficient data, too few inscriptions, no bilingual texts, an extinct language isolate. But what if the problem isn't missing information? What if we've been asking the wrong question?

This paper proposes that Linear A, or significant portions of it, may not encode spoken language at all. Instead, it may function as a multidirectional perceptual instrument, a radial notation system that produces meaning through the geometry of how it's traversed, not through phonetic decoding.

Evidence from interior-inscribed drinking vessels, atmospheric paleoclimate data, and systematic analysis of sign orientation suggests Bronze Age Minoans were encoding something fundamentally different from what later Greek scribes recorded. If true, this would explain not just why decipherment has failed, but why it was never going to succeed using language-based methods.

Abstract

This paper proposes a fundamental reorientation in the study of Linear A, the undeciphered script of Bronze Age Crete (ca. 1800–1450 BCE). Rather than approaching Linear A as a language-encoding system awaiting phonetic decipherment, we advance the hypothesis that it may function as a multidirectional perceptual instrument, a radial notation system designed to produce cognitive coherence in the reader through the geometry of sign arrangement and traversal. We argue that the persistent failure of decipherment efforts stems not from insufficient data or missing bilingual texts, but from a categorical error: the assumption that Linear A is a linear, sequential writing system encoding a spoken language.

We further propose that the environmental conditions under which Linear A emerged may have differed substantially from present-day atmospheric baselines, with implications for human cognition, sensory perception, and the fundamental ratios encoded in measurement systems. Under conditions of greater atmospheric compression and higher vapor density, the relationships between stored commodities, the optical environment in which signs were perceived, and the acoustic space in which language operated would all shift in measurable ways. These shifts would produce notation systems calibrated to conditions that no longer exist, rendering modern interpretive frameworks systematically misaligned.

This paper does not claim to decipher Linear A. It proposes a new interpretive lens and argues that existing approaches may be structurally unable to succeed because they presuppose the wrong category of artifact.

1. Introduction: The Categorical Problem

Linear A has resisted decipherment for over a century. The corpus is small, approximately 1,400 inscriptions, many fragmentary, and the underlying language appears to be a genuine isolate with no confirmed relatives among Indo-European, Semitic, or other known language families. The standard explanation for this failure centers on insufficient data: too few inscriptions, no bilingual Rosetta Stone, and a language with no living descendants.

This paper proposes an alternative explanation. The failure may not be one of insufficient data but of incorrect categorization. Every major attempt at decipherment presupposes that Linear A is a writing system that encodes a spoken language, that its signs represent syllables, words, or concepts in a grammar that, once cracked, will yield readable sentences. This assumption drives the methodological apparatus: frequency analysis of signs is interpreted as phoneme distribution, positional patterns are read as syntax, and sign clusters are parsed as vocabulary.

But what if Linear A, or significant portions of it, is not a language-encoding system at all? What if it is an instrument? Not a record of speech but a structured field of relationships designed to be traversed, producing different information depending on the direction and depth of engagement? This would explain not only the failure of phonetic decipherment but also several anomalous features of the corpus that have resisted satisfying explanation under the language-encoding model.

2. The Environmental Premise

Before addressing the notation system itself, we must consider the conditions under which it emerged. The standard assumption is that Bronze Age atmospheric and environmental conditions were essentially identical to those of the present day, with minor climatic variation. This paper challenges that assumption.

2.1 Atmospheric Compression and Vapor Density

If Earth’s atmospheric history reflects interactions with secondary gravitational planes or inclined celestial systems, then intersecting orbital planes may produce compression zones influencing axial tilt, magnetic orientation, and vapor distribution. These interactions could result in periodic increases in high-altitude vapor density or the emergence of transient atmospheric layers, altering climate behavior and observational baselines without requiring catastrophic surface-level disruptions.

Paleoclimate proxy records provide independent evidence for significant atmospheric variability during the period of Linear A's use. Greenland ice core data (GISP2) indicate sustained variability in atmospheric sulfate loading and volcanic aerosol deposition across this period (Zielinski et al. 1994). Speleothem data from Mediterranean caves and Nile flood records synchronized to Minoan chronology document episodes consistent with elevated atmospheric moisture across the eastern Mediterranean (Rohling et al. 2002; Manning 2010). The Minoan period coincides with one of the most volcanically active phases in Holocene Mediterranean history, including the Theran eruption (variously dated to 1628–1530 BCE), which injected massive quantities of aerosols and water vapor into the regional atmosphere with documented effects on optical transmission, solar attenuation, and climate patterns lasting years to decades (Oppenheimer 2003; Manning et al. 2006). None of this constitutes direct evidence for the specific atmospheric conditions proposed here. It does, however, establish that the optical and atmospheric environment of Bronze Age Crete was not identical to that of the present day, and that the differences were neither trivial nor transient.

The pattern of bifurcated orbital planes, anomalous retrograde objects, and planetary axis drift suggests a recurring geometric interaction not fully accounted for by current heliocentric frameworks. Systems behaving as if under intermittent external torque point to slow, elliptical, or inclined influences. The compression and vapor modulation pattern is consistent across independent mythological, observational, and geophysical threads. For the purposes of this paper, we adopt the working hypothesis that the Minoan period may have experienced higher atmospheric vapor density and different effective surface compression than the present. The implications of this hypothesis for human cognition and notation systems are explored in the following sections.

2.2 Cognitive Implications of Altered Atmospheric Conditions

If atmospheric conditions were substantively different during the period of Linear A’s development and use, the consequences extend far beyond climate. Human cognition is not independent of environment, it is a function of it.

Visual processing is shaped by available light, atmospheric scattering, and contrast ratios. Under a higher-vapor atmosphere, direct solar radiation reaching the surface would be reduced. Light would scatter more broadly, producing a more diffuse, evenly illuminated visual environment with softer shadows and lower contrast. The human visual system adapts to its operative conditions. A writing system developed for legibility in diffuse light would differ in fundamental ways from one designed for high-contrast direct sunlight, rounder, more flowing forms rather than sharp angular ones. The observed difference between the rounder character of Linear A signs and the crisper angularity of the later Linear B system may reflect not merely cultural evolution but a genuine shift in optical environmental conditions between the two periods.

Additionally Cretan Hieroglyphic's heavy reliance on iconic, asymmetric forms, animals facing, limbs gesturing, objects oriented, suggests a notation born in an optical regime where directionality and relational facing carried immediate perceptual weight. As atmospheric conditions evolved, Linear A retained these directional echoes in its oldest strata, even as administrative needs favored symmetry and sequence. Regional paleographic variation (SigLA-documented) may thus encode not just scribal habits, but localized perceptual calibrations to light scattering, contrast, and vapor-mediated visibility.

Auditory processing changes with air density and sound propagation speed. Under higher atmospheric pressure and vapor content, the speed of sound increases and acoustic properties of the environment shift. If any phonetic components exist within Linear A, they would map to a different acoustic space than modern linguists assume. Attempts to reconstruct pronunciation from sign frequency analysis would be calibrated to the wrong baseline, producing systematic drift mistaken for linguistic isolation.

Even proprioception, the felt sense of one’s own body in space, shifts under different atmospheric pressure. The relationship between a human being and their physical environment is not constant. It is a function of the medium they inhabit.

2.3 Developmental Implications

The implications of altered atmospheric conditions extend to human development itself. Children raised under different atmospheric compression, different light exposure patterns, and different acoustic environments would develop differently at a physiological level. Visual cortex wiring is a function of available light during critical developmental periods. Circadian rhythms, hormonal development, and neurological maturation are all sensitive to atmospheric and optical conditions. Spatial perception and proprioceptive calibration, governed in part by inner ear development under ambient pressure conditions, would produce individuals whose felt sense of space and relationship differed from that of modern humans.

If a notation system were designed to serve both children and adults within such an environment, it would need to accommodate developmental stages calibrated to those conditions. A radial, multidirectional system, one that a child could enter at a basic level of engagement and an adult could traverse at deeper levels, would serve this purpose naturally. Children process information relationally before sequential processing is trained into them; a system designed to work with, rather than against, this developmental trajectory would be radial by necessity.

3. The Radial Hypothesis

3.1 Against Linearity

The term “Linear A” itself embeds an assumption, that the script is linear, that it encodes information sequentially, to be read in one direction from a defined start point to a defined end point. This assumption was inherited from Linear B, where it is largely justified by the administrative tablet format and the known properties of the Mycenaean Greek it encodes. It was then projected backward onto Linear A.

However, Linear A appears on a wider variety of supports and in a wider variety of contexts than Linear B. While Linear B is restricted to administrative documents, Linear A appears on tablets, roundels, sealings, libation vessels, and other ritual objects. The non-administrative inscriptions, particularly those on ritual vessels, exhibit spatial arrangements that do not conform to the linear, sequential model.

Certain inscriptions display radial or center-oriented spatial organization. Signs are arranged not in rows to be read sequentially but in spatial relationships to a central form or to each other. This paper proposes that this arrangement is not decorative or incidental but functional. The spatial organization of signs carries meaning, and the direction of traversal through the sign field produces different readings.

3.2 Multidirectional Reading

“Linear” does not merely describe the script’s graphic form. It describes an assumption about information flow: one direction, sequential, start here, end there. A radial system operates differently. A reader can enter from any point on the periphery and move toward the center, start at the center and move outward, read across through the center from one side to another, or spiral. The path through the information is not prescribed, it is chosen by the reader based on what they need.

This distinction is the difference between a language and an instrument. A language tells you something in one direction. An instrument allows you to extract different information depending on how you engage with it. You read a sentence. You use a diagram. If Linear A is multidirectional, then portions of it may not be something one reads, they are something one uses. The information derived depends on the direction of traversal.

This may well explain why decipherment has failed. One cannot decipher an instrument. One can only learn to operate it. And one cannot learn to operate it without understanding the conditions it was designed to operate within.

3.3 Perception Transduction Projection Framework

If the notation is radial and multidirectional, it is not storing information for retrieval in the conventional sense. It is structuring perception itself. The act of engaging with the notation, moving the eyes through the sign field along different paths, produces cognitive events in the reader. The reading is the cognition. Not a record of someone else’s thoughts, not a transmission of information from writer to reader, but a structured experience that generates understanding through the process of traversal.

This framework, perception transduction projection (PTP Framework, Symfield, Flynn 2025), treats the notation as a technology for producing specific cognitive states. The signs are arranged so that moving through them in particular patterns produces particular kinds of understanding. This is fundamentally different from encoding and decoding, which is the model underlying all current decipherment attempts.

Under this model, the notation would be designed to function for readers at different developmental stages. A child entering the sign field at a basic level of perceptual maturity would extract one layer of meaning. An adult with deeper training would traverse more complex paths and extract richer understanding. The same inscription serves multiple audiences simultaneously, not because it contains hidden messages but because radial, multidirectional information naturally yields different depths depending on the reader’s capacity.

In ritual supports, cups, libation tables, seals, the act of viewing/traversing the sign field integrates with bodily engagement (drinking, rotating, impressing). This embodied multi-directionality echoes Cretan Hieroglyphic's use on dynamic objects, where signs activate through interaction rather than passive decoding.

4. The Coordinate Model: Sign Function as Spatial Relationship

4.1 Against Fixed Sign Identity

Modern analysis of Linear A presupposes distinct functional categories for signs: syllabograms (a sign representing a spoken syllable, as distinct from a logogram, which represents a whole word or concept, and an ideogram, which represents a thing or quantity directly), logograms (signs standing for entire words or concepts), numerals (signs representing quantities), and metrical signs (signs representing units of measurement or fractions). This categorical framework is inherited from the successful decipherment of Linear B, where such distinctions are largely justified by the underlying Greek language.

However, the projection of these categories onto Linear A introduces a structural assumption that may not hold: that each sign has an intrinsic, fixed functional identity, that a given sign is inherently a syllabogram, or inherently a numeral, or inherently a logogram. The well-documented “multi-functionality of signs based on context” noted in the SigLA database and throughout the scholarly literature is typically treated as an analytical complication rather than a fundamental property of the system.

This paper proposes the alternative: that multi-functionality is not a complication but the core operating principle. If sign function is determined not by intrinsic identity but by spatial relationship to a fixed reference point, an anchor, then the same sign in different positions relative to that anchor would perform different functions. Not because it switches between modes, but because what modern analysis categorizes as separate functions (phonetic, logographic, numerical) may be aspects of a single unified sign function that expresses differently depending on relational context.

4.2 The Anchor Principle

A coordinate-based reading model requires a reference point, an anchor against which all other signs are positioned and from which their function is derived. In a radial system, this anchor is the center. Every sign cluster on the inscription surface has a spatial relationship to the center point: distance from center, angular position, and orientation relative to adjacent clusters.

If meaning is a function of these spatial relationships rather than of sequential position in a string, then an inscription is not a sentence to be parsed but a field to be navigated. Each cluster is read not in isolation and not in sequence but in its relationship to the anchor. The same cluster, if its angular position or distance from center changed, would yield different information, not because the signs changed but because the relationship changed.

This model predicts specific observable properties. Sign clusters on the same inscription should demonstrate consistent geometric relationships to the central axis. Signs appearing in different clusters at different distances from center but at similar angular positions should exhibit functional relationships. And the anchor itself, whether physically marked or implied by the geometry of the inscription surface, should be identifiable as a structural constant across specimens.

4.3 The Interior-Inscribed Vessel as Evidence

The cup inscription documented by Arthur Evans at Knossos in 1909, an ink-written inscription on the interior surface of a drinking vessel, provides a compelling case study for the coordinate model. Scholarly analysis notes that the inscription follows a spiral alignment adapted to the cyclic surface, that the text was designed to be read by the cup’s user only, and that it can only be fully read when the cup is empty or progressively revealed as the user drinks and rotates the vessel.

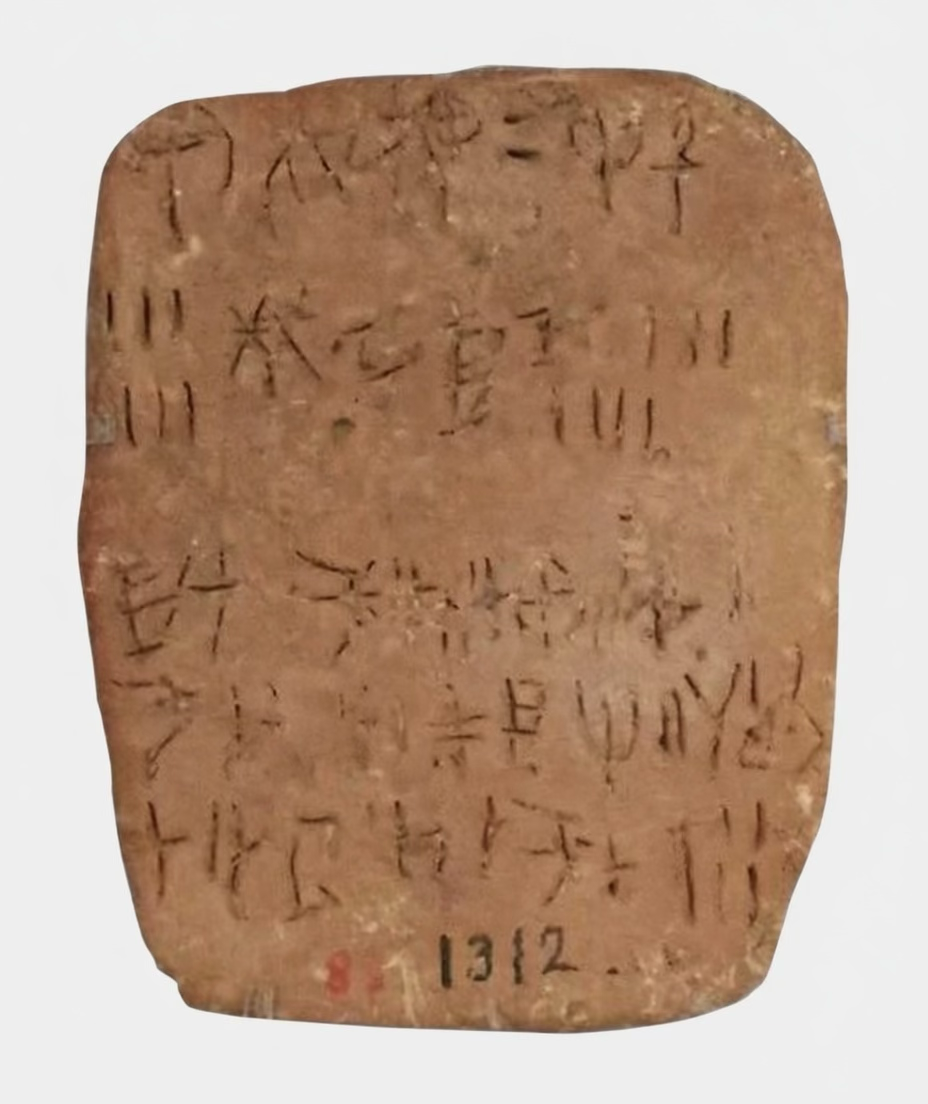

Figure 1A: Clay drinking cup with a Linear A inscription painted with sepia ink. Found at Knossos, Crete. Middle Minoan IIIa (ca. 1700 BCE).

Clay drinking cup with a Linear A inscription painted with sepia ink. Found at Knossos, Crete. Middle Minoan IIIa (ca. 1700 BCE).

- Instance of: cup

- Made from material: clay

- Time period: ca. 1700 BCE

- Diameter: 8.4 cm

- Collection: Heraklion Archaeological Museum

- Inventory number: KN Zc 6 / HM P2630

Under a sequential reading model, this inscription is an awkwardly formatted text constrained by an inconvenient surface. Under the coordinate model, it is a precisely engineered instrument. The center of the cup’s interior is the anchor. Sign clusters arranged on the interior surface are positioned at specific distances and angles relative to that center. The liquid in the cup is not incidental but functional, when the vessel is full, the anchor is submerged and invisible. As the user drinks, the anchor progressively reveals itself. The relationship between each sign cluster and the anchor changes, not because the signs move but because the anchor transitions from hidden to visible.

This produces a dynamic notation system in which the state of the vessel, full, partially consumed, empty, is a variable in the reading. The same sign clusters yield different information depending on whether the anchor is visible or concealed. The inscription is not static but state-dependent. The physical act of consuming from the vessel is integrated with the act of engaging the notation.

The use of ink rather than incision further supports this interpretation. Ink-written inscriptions are less durable than incised ones, suggesting that this inscription was meant for active use in the present rather than permanent archival. It was designed to be experienced, not stored.

4.3.1 Glyph Orientation and Reading Direction

The administrative tablets of the Linear A corpus are conventionally read left to right, a determination based on sign alignment, spacing patterns, and analogy with Linear B. This convention appears well-supported at the level of line-by-line sequence: sign clusters progress from left to right across tablet registers in a manner consistent with administrative list-making.

Figure 2. Minoan clay tablet inscribed with Linear A (HT 8, Hagia Triada). On display at the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, Crete. Photograph: Ester Salgarella. Note the left-to-right progression of sign clusters across tablet registers. Section 4.3.2 discusses the relationship between line-level reading direction and the internal orientation of individual signs.

However, the orientation of individual signs within this sequence raises a question that has received less systematic attention. In Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, glyph-internal orientation operates independently of line-level reading direction, signs face toward the beginning of the line, providing an internal directional indicator that scholars use to determine reading order (Allen 2014). The principle that individual sign orientation and macro-level reading direction can function as separate systems is therefore well established in the study of ancient scripts.

Preliminary visual inspection of Linear A tablets (Figure 2) suggests that a similar investigation may be warranted for Linear A. While the sequence of sign clusters proceeds left to right, the internal geometry of individual signs does not uniformly conform to this direction. Some signs appear to orient in opposition to the reading direction or to exhibit non-directional symmetry properties that do not privilege any single axis of approach.

If confirmed through systematic paleographic analysis, this observation would carry significant implications for the interpretive framework proposed here. A system in which macro-level reading proceeds sequentially (left to right across a tablet line) while micro-level sign orientation operates independently or multi-directionally would be consistent with a notation system whose fundamental units, the individual glyphs, were not originally designed for sequential reading but were adapted to it for specific administrative purposes. The glyphs may retain structural properties of an earlier or parallel non-sequential usage, properties visible on artifacts such as KN Zc 6, where no left-to-right convention applies.

While many core syllabic signs in Linear A have been smoothed into bilateral symmetry for the convenience of linear administrative flow, it is precisely the most asymmetric glyphs, the ones still carrying directional ‘facing’ or leaning bias, that cluster among the oldest, picture-derived forms inherited from Cretan Hieroglyphic. These are not accidents or scribal quirks; they are survivors. They remember a time before the script was forced into left-to-right chains, when directionality itself was semantic, when a sign could face toward an anchor, a viewer, a path of traversal, or the center of a radial field. The deeper we look, the clearer it becomes: the oldest signs are whispering the original grammar of the system, and that grammar was never linear. Direction wasn’t decoration; it was meaning. And the oldest glyphs still know which way to face.

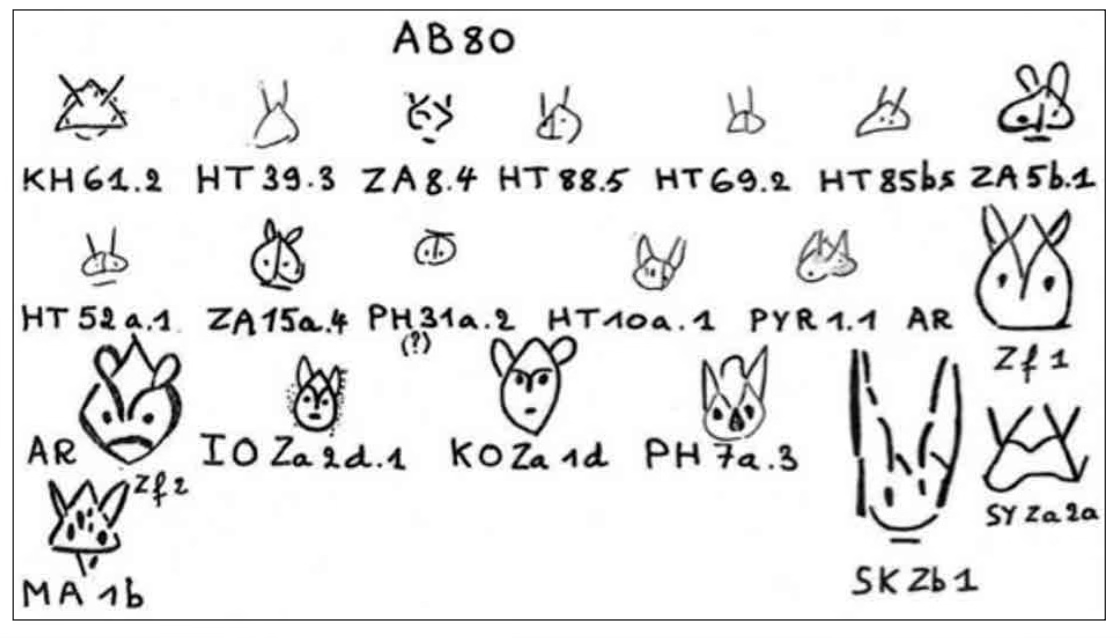

Linear A did not emerge in isolation; it condensed from the more overtly pictorial and directionally expressive Cretan Hieroglyphic corpus (ca. 2000-1700 BCE), where signs retained strong iconicity, inherent facing, and compositional freedom on seals and objects. While administrative Linear A streamlined many forms into symmetry for sequential efficiency, the asymmetric, 'facing' or leaning glyph, those with protrusions, heads, branches, or directional bias, cluster disproportionately among the picture-derived strata inherited from Cretan Hieroglyphic. These are not vestigial quirks. They are stratigraphic survivors: the oldest layers of the script, closest to its pre-administrative genesis, still encoding a directional semantics that radial traversal could activate. In a multidirectional perceptual instrument, a sign's internal orientation is not noise, it is a vector, pointing toward anchors, paths, or relational fields rather than chaining in fixed sequence. The deeper the paleographic lineage, the louder the whisper of non-linearity.

4.3.2 Variants Span a Continuum: Iconic vs. Abstract Renderings in Paleographic Perspective

Recent work on Cretan Hieroglyphic seals provides a compelling precedent for questioning rigid Paleographic unification. Ferrara and Weingarten (2022), in an ERC-funded analysis, advocate treating inscribed seals as multimodal systems where glyptic (visual/iconic) and epigraphic (sign-based) elements interact dynamically rather than hierarchically. Seals, often prisms or cushions with signs arranged across faces, orbiting central motifs, or facing inward/outward, exhibit non-linear, multidirectional layouts that activate through rotation, impression, and relational viewing. Drawing on material from Myrtos-Pyrgos and eastern Cretan sites, this integrated approach challenges the separation of “script” from “decoration” and highlights how sign orientation, facing, and context contribute to meaning beyond sequential decoding.

Such multimodal dynamics echo in Linear A non-administrative contexts (e.g., spiral rings, radial roundels) and support re-examining variants like AB80. The paper’s emphasis on local trends and selective abstraction of iconic forms (e.g., animal motifs persisting with directional bias) suggests that Paleographic divergence may reflect functional or perceptual distinctions rather than mere scribal noise, precisely the categorical complexity our radial framework seeks to recover.

GORILA documents significant variation in the rendering of individual signs across sites. For example, sign AB80 is attested in forms ranging from clearly iconic (recognizable animal imagery with ears, whiskers, facial features, and directional “facing,” suggestive of cat- or rabbit-like forms echoing Cretan Hieroglyphic animal-head signs) to purely abstract (geometric configurations of prongs, lines, and angles sharing certain structural features but no pictorial resemblance). The standard interpretation classifies all such variants as a single sign with consistent phonetic value. An alternative possibility, that iconic and abstract renderings represent functionally distinct uses of overlapping graphic elements, has not been systematically investigated. If some variants function as images carrying inherent meaning through resemblance and orientation, while others operate as positional or relational markers whose significance derives from position, facing, or traversal path, the classification of all variants under a single sign identity may obscure a functional distinction embedded in the original system.

This potential bifurcation aligns with the script's Cretan Hieroglyphic precursors, where animal-head signs frequently appear on seals in multidirectional contexts, facing inward toward central motifs, orbiting on prism faces, or arranged in non-sequential clusters. If AB80's variants preserve a functional split between iconic (perceptual/representational) and abstract (positional/spatial) roles, then the sign list itself flattens an original categorical complexity. Systematic comparison of iconic vs. abstract AB80 contexts (e.g., co-occurrence with anchors, radial arrangements, or non-administrative supports) could test whether orientation or function differs systematically between the two types, revealing whether the shared graphic kernel masks divergent semiotic behaviors.

Figure 3 AB80 attestations: Iconic survivors vs. abstract notation? Variants range from recognizable animal imagery (cat/rabbit heads with directional facing and asymmetry, likely inherited from Cretan Hieroglyphic feline signs) to non-pictorial geometric forms (shared strokes but no resemblance). If iconic and abstract renderings serve different functions, one perceptual/representational, the other relational/spatial, the unified sign identity in GORILA and SigLA may mask an original categorical complexity. Hand-drawn compilation after paleographic data in Godart & Olivier (1976-1985, GORILA V) and SigLA (Salgarella & Castellan 2020-present), including examples from HT, ZA, PH, IO, PYR, and others.

4.4 KN Zc 6 case study

The following section contains preliminary interpretive observations on specific Linear A signs and configurations. These are offered as speculative propositions intended to illustrate the application of the radial and coordinate-based frameworks, not as claims of decipherment.

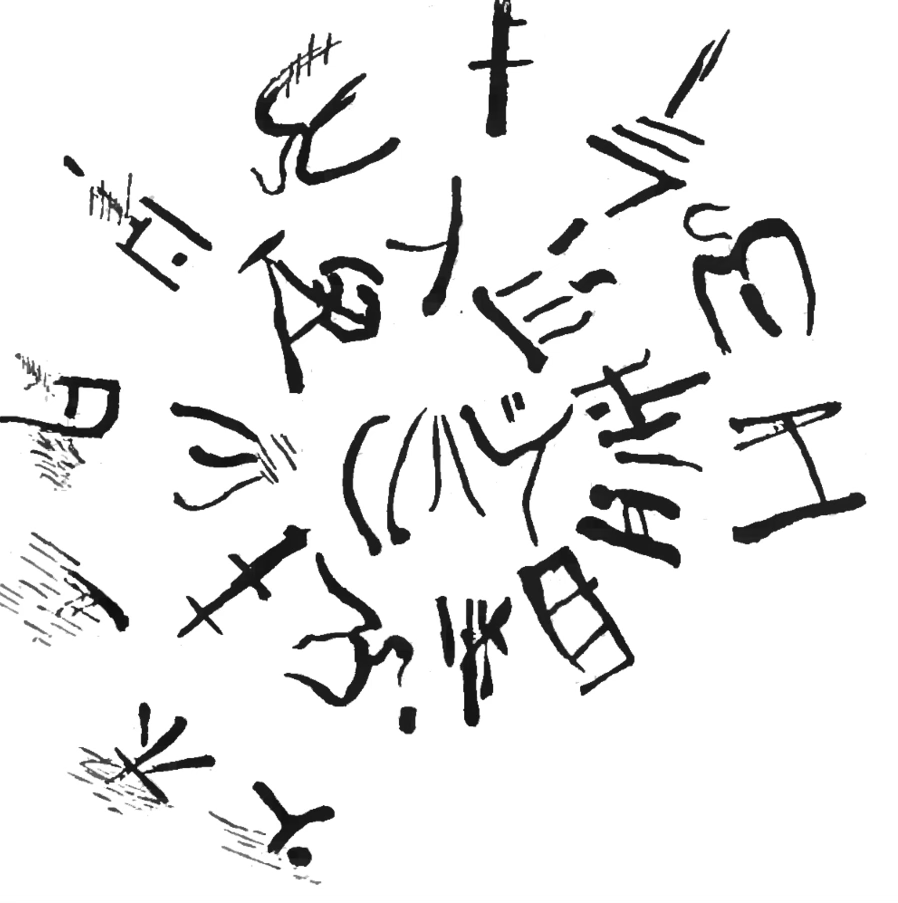

Figure 4. Ink-written Linear A inscription on the interior surface of a cup, Knossos. After Evans (1909). Note the radial arrangement of sign clusters around a central axis and the spiral alignment adapted to the cyclic surface.

Figure 4 Note. This inscription is also known as KN Zc 6 (HM 2630), dated MM III (ca. 1700–1600 BCE). A processed drawing of KN Zc 6 appears as the cover image of the first dedicated Linear A volume: Salgarella, E. and Petrakis, V., eds. (2025). The Wor(l)ds of Linear A: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Documents and Inscriptions of a Cretan Bronze Age Script. AURA Supplement 15. Athens: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Cover caption: "Drawing of the inscription on KN Zc 6 (image after SigLA, with further processing)." Full paleographic documentation of KN Zc 6 is available at https://sigla.phis.me/document/KN%20Zc%206/

The SigLA database records KN Zc 6 as containing 23 signs divided into four "words," with every sign classified as a syllabogram, a phonetic sign representing a syllable. This classification derives from backward projection, because certain Linear A signs resemble Linear B signs, and because Linear B encodes Mycenaean Greek with known phonetic values, those values are assigned to the visually similar Linear A signs. The method is acknowledged as provisional throughout the literature (Steele and Meißner 2017), yet it operates in practice as the default analytical framework.

Several features of this classification merit scrutiny. First, two of the 23 signs on KN Zc 6, designated *34 and *79, receive no phonetic assignment because they lack Linear B equivalents. They are numbered but unread. A framework that cannot classify approximately nine percent of the signs on a given inscription within its own categories may be encountering the limits of its applicability rather than gaps in available data.

Second, the division into four "words" presupposes that the marks separating sign clusters function as word dividers, that the clusters between separators are linguistic units representing elements of spoken language. This is a reasonable interpretation if one has already determined that the inscription encodes language. If one has not, and in the case of Linear A, the underlying language remains unidentified, then the separators may demarcate something other than words. They may define relational clusters, spatial zones, or functional groupings whose significance depends on position relative to the inscription surface rather than on sequential reading order.

Third, the uniform classification of every sign as "syllabogram" applies a single functional category across the entire inscription. This presupposes that every sign on KN Zc 6 performs the same type of function, encoding a syllable in a spoken word. Yet the inscription appears on the interior of a drinking vessel, arranged in a spiral pattern around a central axis, written in ink by a scribe using techniques Evans himself described as "independent methods and forms, somewhat variant from that of the other school of scribes" (Evans 1901–1902, 109). The medium, the spatial arrangement, and the method of production all distinguish this inscription from administrative tablets. Whether the analytical categories developed for tablets apply without modification to a radial inscription on a ritual vessel is an open question that warrants direct investigation.

None of this diminishes the paleographic achievement represented by SigLA and the broader corpus documentation. The sign-by-sign recording, the variant tracking across sites, and the open-access dataset are essential infrastructure for any future analysis, including the one proposed here. What is questioned is not the data but the interpretive layer applied to it, specifically, whether the categories of syllabogram, word, and sequential reading adequately describe what is occurring on the interior surface of KN Zc 6, or whether they represent the projection of a framework designed for one class of inscription onto a fundamentally different class of artifact.

4.4.1 Side By Side Observations

Figure 1a. Interior of KN Zc 6 (HM 2630), clay drinking cup with Linear A inscription in sepia ink, Knossos, ca. 1700 BCE. Diameter 8.4 cm. Photograph courtesy of Heraklion Archaeological Museum / Things That Talk.

Figure 4. Drawing of the inscription on KN Zc 6, showing sign clusters in flattened projection. After Evans (1909); cf. SigLA (Salgarella and Castellan 2021).

Note the difference between the photographic record, which preserves the three-dimensional spatial relationship of sign clusters to the cup's interior surface and central axis, and the linear drawing, which necessarily flattens these relationships into a two-dimensional representation. The coordinate model proposed in this paper concerns properties visible in 1a that are structurally absent from 1b.

4.5 Unified Sign Function: Beyond the Number-Letter Distinction

The persistent separation of phonetic, logographic, and numerical functions in Linear A analysis may reflect a categorical assumption inherited from modern notation systems rather than an inherent property of the original script. Modern writing systems maintain strict separation between alphabetic signs (encoding sound), numerical signs (encoding quantity), and symbolic signs (encoding concepts). This separation is so fundamental to modern literacy that it is rarely questioned as an analytical premise.

However, this separation is a design choice, not a universal necessity. It reflects a particular cognitive framework in which the qualitative nature of a thing and its quantitative measure are treated as fundamentally different categories of information requiring different notational systems. An alternative framework, one in which quality and quantity are understood as aspects of the same underlying reality rather than as separate domains, would produce a notation system in which a single sign carries both qualitative and quantitative information simultaneously.

Under such a system, a sign read in one relational context (one position relative to the anchor, one cluster configuration) would yield what modern analysis categorizes as a “word” or “concept.” The same sign read in a different relational context would yield what modern analysis categorizes as a “number.” The sign itself does not switch between functions. Rather, what modern analysis perceives as two distinct functions is a single unified function that modern categorical frameworks lack the apparatus to perceive as unified.

This would account for one of the most persistent puzzles in Linear A analysis, the apparent co-occurrence of “numerals” and “commodity signs” in configurations consistently interpreted as inventory or accounting records. Under the unified sign function model, these configurations are not lists of things plus quantities. They are unified expressions in which the nature of what is described and the measure of it are inseparable, a single sign or cluster expressing the full relationship between a phenomenon and its magnitude.

If the original system did not make these distinctions, then any analysis built on that separation would systematically misclassify signs whose function is determined by relational context rather than intrinsic identity. The search for a one-to-one mapping between signs and fixed meanings, the foundational method of decipherment, would be structurally incapable of succeeding, not because the data is insufficient but because the method presupposes a sign architecture that does not match the system being analyzed.

5. The Measurement Problem

5.1 Fractional Ratios Under Different Physical Regimes

Linear A’s numerical system includes fractional notations that have resisted clean interpretation. The fractions appear internally consistent but do not map onto base-10, base-60, or other standard ancient numerical systems. Some fractions appear to shift depending on the commodity being measured, leading scholars to propose separate dry and liquid measurement systems.

Under the environmental premise of this paper, a simpler explanation presents itself. If atmospheric compression and vapor density were different, then the physical behavior of commodities changes. Grain stored under higher atmospheric pressure and humidity compacts differently, absorbs moisture differently, and the ratio between volume and weight shifts. Oil viscosity changes under different atmospheric pressure. The ratio between a unit of oil and a unit of grain would be genuinely different because the substances are physically behaving differently.

If the Minoans were measuring under those conditions and their units reflect empirical accuracy for that environment, then modern scholars reconstructing their measurement standards against current atmospheric baselines would consistently produce slight mismatches, which is precisely the pattern observed in Linear A numerical analysis.

5.2 A Testable Proposition

The fractional and numerical relationships in Linear A constitute a dataset that has been analyzed as abstract mathematics. But these weren't abstractions to the Minoans, they were measurements of physical substances under real conditions. Grain compacts differently under different atmospheric pressure. Oil viscosity shifts with temperature and humidity. The ratio between volume and weight for any stored commodity is a function of the environment in which it sits.

This suggests a reversal of the usual analytical direction. Rather than asking "what do these numbers mean?", ask "under what physical conditions would these specific ratios be empirically accurate?" Model the known fractional relationships against variable atmospheric parameters. If a consistent environmental regime emerges, one set of conditions under which the tablet mathematics becomes physically coherent across different commodity types, that regime becomes a testable hypothesis about Bronze Age Crete's actual atmospheric state.

6. Regional Variation as Perceptual Accuracy

The SigLA database, developed by Ester Salgarella and Simon Castellan, meticulously documents paleographic variation in Linear A signs across sites, Hagia Triada, Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia, Zakros, and Khania. The same sign appears in recognizably different graphic forms depending on where it was inscribed. The standard interpretation treats this as scribal variation, regional dialect, or evolutionary drift.

Under the framework proposed here, an alternative explanation emerges. If atmospheric and environmental conditions varied regionally, which they would under any non-uniform compression or vapor density model, then people in different locations were having genuinely different perceptual experiences. Their visual processing was calibrated to different optical conditions. Their acoustic environment differed. Their felt sense of spatial relationships differed.

If notation encodes perceptual experience rather than (or in addition to) linguistic content, then regional variation is not drift or dialectal difference. It is accuracy. Each region’s scribes were faithfully recording from within their own perceptual conditions. The variation documents real differences in how reality was experienced at different locations.

7. The Material Evidence

7.1 Clay as Atmospheric Record

The tablets themselves, their material properties, how the clay responds to stylus pressure, how deep inscriptions are incised, how fine the detail can be, are all functions of atmospheric conditions during manufacture. Denser atmosphere means different combustion behavior for kiln-fired clay. Different humidity affects clay plasticity and drying behavior. The physical characteristics of the tablets constitute data about the environment in which they were made.

A systematic material science analysis of Linear A tablets, clay composition, firing characteristics, incision depth and precision as functions of atmospheric pressure and humidity models, has not been conducted within this framework. Such an analysis could provide independent physical evidence for or against the environmental premise proposed here.

7.2 Architectural Context

The relationship between the notation and the built environment deserves attention. If Linear A functions in part as architectural or structural notation, encoding relationships relevant to how things are built, how forces operate, how materials behave under specific conditions, then the find contexts (storage rooms, workshops, archive areas adjacent to construction and production spaces) take on additional significance beyond mere bureaucratic record-keeping.

8. Chronological Context: Linear A and Environmental Transition

Linear A’s conventional dating, ca. 1800 to 1450 BCE, places its emergence in a period of significant transition in the ancient Mediterranean. The script appears to emerge in the aftermath of major regional disruptions and persists through a period of palace-centered civilization before ceasing abruptly around 1450 BCE.

A note of caution is warranted regarding the precision of these dates. Establishing an absolute chronology for Bronze Age Crete has proved difficult. The standard method synchronizes Minoan relative chronological periods with those of better-documented neighbors, particularly Egypt, by matching co-occurring artifacts. However, dates determined through such synchronization do not always agree with results from radiocarbon dating and other methods based on natural science (see the ongoing debates in Manning 2014; Wiener 2015). The discrepancies are not trivial. They can span decades or more, and they remain unresolved. Any argument that links Linear A’s chronological boundaries to specific environmental or atmospheric transitions must acknowledge that the boundaries themselves carry significant uncertainty. The dates used throughout this paper are conventional estimates, not settled facts.

If the environmental premise of this paper holds, then Linear A’s chronological boundaries may correspond not merely to political or cultural transitions but to shifts in atmospheric conditions. The script may have been developed as a response to changing environmental circumstances, a new notation technology created by people who needed to encode knowledge under conditions significantly different from what preceded them. Its cessation around 1450 BCE and replacement by Linear B may reflect not merely Mycenaean political dominance but a subsequent environmental shift that rendered the earlier notation system less functional or less aligned with the prevailing perceptual conditions.

This interpretation reframes the relationship between Linear A and Linear B. Rather than viewing Linear B as an evolutionary development from Linear A, or as a colonial imposition, we might understand the two systems as notation technologies calibrated to different environmental regimes. Linear B’s more angular, crisper sign forms and its strictly sequential, administrative character may reflect adaptation to a higher-contrast, lower-vapor optical environment, conditions under which a radial, multifunctional notation system would be less necessary and a linear, fixed-function system would be more practical.

9. Implications for Decipherment

If the hypothesis advanced in this paper is correct, even partially, it has significant implications for all decipherment efforts.

First, approaches that assume Linear A encodes a single spoken language in a linear, sequential format may be structurally unable to succeed, not because of insufficient data but because of incorrect categorization. The system may be doing multiple things simultaneously: encoding sound in some positions, describing spatial relationships in others, recording dynamic processes in others. The reason it resists decipherment may be that scholars keep trying to make it be one kind of thing when it is actually several kinds of thing operating in an integrated notation.

Second, the projection of Linear B values onto Linear A signs, the assignment of phonetic values and commodity labels based on graphic similarity between the two systems, may introduce systematic error. Linear A is older, comes from a different civilization operating under potentially different physical conditions, and may not share semantic content with Linear B despite sharing some visual similarity in sign forms.

Third, computational and AI-based approaches to decipherment (including the recently developed Zakros AI system built on the SigLA and GORILA corpora) inherit these assumptions. If the training data and analytical frameworks presuppose a language-encoding model, then AI systems will reproduce and amplify the categorical error rather than correcting it.

What may be needed is not more sophisticated language-decoding algorithms but a fundamentally different kind of analysis, one that treats the sign fields as geometric and relational structures, examines them for multidirectional coherence, and tests whether the numerical relationships they contain become physically meaningful under different environmental parameters.

10. Testable Predictions

The framework proposed in this paper generates several specific, testable predictions:

First, interior-inscribed vessels: if additional specimens of interior-inscribed vessels exist in the corpus or can be identified in museum collections, sign clusters on these vessels should demonstrate consistent geometric relationships to the central axis of the vessel interior. The angular positions and distances of clusters relative to center should exhibit patterns that are not explained by sequential reading models.

Second, cross-specimen anchor consistency: across different inscription-bearing objects, identifiable anchor points (whether physically marked or implied by the geometry of the inscription surface) should be structurally consistent. The anchor principle should hold across media types.

Third, atmospheric measurement coherence: if the known fractional and numerical relationships in Linear A are modeled against variable atmospheric parameters (pressure, humidity, temperature), there should exist a range of atmospheric conditions under which the ratios become physically coherent as empirical measurements of real commodity behavior. This range should be internally consistent across different commodity types.

Fourth, material science correlation: analysis of tablet physical properties (clay composition, firing characteristics, incision precision) should correlate with atmospheric models in ways that are consistent with the environmental premise.

Fifth, sign function variability: the same sign appearing in different spatial positions relative to identifiable anchor points should exhibit functional variation that is systematic and predictable from position, rather than random or context-independent.

Sixth, Systematic analysis of Cretan Hieroglyphic seal compositions should reveal sign orientations aligned to radial axes or central motifs rather than to linear reading direction, consistent with the anchor-based coordinate model proposed here.

11. Limitations and Open Questions

This paper is a theoretical proposal, not a completed analysis. Several significant limitations must be acknowledged.

The environmental premise, that atmospheric conditions during the Minoan period differed substantially from the present, requires independent physical evidence. While the framework proposed here generates testable predictions (measurement ratio analysis, material science investigation of tablet properties, systematic comparison of sign geometry with optical environment models), these tests have not yet been conducted.

The radial hypothesis is proposed on the basis of spatial arrangement patterns observable in certain Linear A inscriptions, particularly those on non-administrative supports. It does not necessarily apply to the entire corpus. Administrative tablets with clearly tabular formats may indeed function as sequential records. The proposal is that the corpus is not homogeneous, that different classes of inscription may be doing fundamentally different things.

The question of sacred and cultural ownership must also be acknowledged. These inscriptions were created by a civilization we do not fully understand, for purposes we cannot confirm. Any interpretive framework must be held with appropriate humility and offered as a lens for exploration rather than a claim of possession.

12. Conclusion

Linear A has remained undeciphered for over a century. This paper proposes that the failure may stem from a categorical error rather than insufficient data. By assuming Linear A is a linear, language-encoding writing system, scholars may have precluded the possibility of recognizing what it actually is.

Under an alternative framework, one that takes seriously the possibility of different environmental conditions, the implications of those conditions for human cognition and perception, and the evidence of radial and multidirectional spatial organization in the inscriptions themselves, Linear A emerges as something potentially more complex and more sophisticated than a writing system. It may be an instrument for structuring perception, a notation that produces understanding through the geometry of traversal rather than the decoding of symbols.

Every phase state is a lens to every other phase state. There is no such thing as singular. Some things are more directly correlated to us than others. This one feels further away. But distance does not imply inaccessibility, it implies the need for a different path. The path proposed here begins not with the signs themselves but with the conditions that gave rise to them, and asks what becomes visible when we look through a lens calibrated to a reality we may have forgotten existed.

The framework proposed here may ultimately prove incomplete or incorrect. But the questions it raises, whether Linear A's spatial properties constitute functional architecture rather than decorative arrangement, whether sign categories inherited from a younger script adequately describe an older one, whether the persistent failure of decipherment reflects insufficient data or an incompatible analytical premise, these questions do not depend on the answers this paper proposes. They depend only on the willingness to ask them. The physics of how information encodes, transmits, and resolves through relational structure does not care what century finds it.

The Rig Veda's Nasadiya Sukta, composed during or shortly after Linear A's period of use, preserves a voice willing to hold cosmological uncertainty without resolution:

"Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it? Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation? The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe. Who then knows whence it has arisen? Perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not, the one who looks down on it, in the highest heaven, only he knows. Or perhaps he does not know."

If Bronze Age cultures possessed linguistic and notational frameworks for preserving rather than eliminating ambiguity, then our inability to "decipher" Linear A may indicate not deficiency in the script but limitation in our analytical apparatus. We keep demanding collapse into singular meaning from a system that may have been designed to resist it.

It says, here's evidence that non-collapse expression existed in the ancient Mediterranean world, and if it did, then maybe our inability to read Linear A says more about our tools than about their script.The structural properties described here, signs maintaining multiple simultaneous functional states until relational context resolves them, notation producing meaning through traversal rather than sequential decoding, suggest that formal frameworks designed to preserve rather than eliminate ambiguity may prove more adequate to this system than collapse-based approaches.

References

Salgarella, E. and Castellan, S. (2020). “SigLA: The Signs of Linear A, A Paleographical Database.” In: Grapholinguistics in the 21st Century 2020. Proceedings. Fluxus Editions, Brest, pp. 945–962.

Salgarella, E. (2020). Aegean Linear Script(s): Rethinking the Relationship Between Linear A and Linear B. Cambridge University Press.

Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P. (1976–1985). Recueil des inscriptions en linéaire A (GORILA). Études crétoises, vols. 21.1–21.5. Paris.

Younger, J. G. Linear A Texts in Phonetic Transcription. University of Kansas. [Online resource, continuously updated.]

Corazza, M., Ferrara, S., Ferro, L., Montecchi, B., Tamburini, F., and Valério, M. (2021). “The Mathematical Values of the Linear A Fraction Signs.” Journal of Archaeological Science, 125.

Evans, A. J. (1909). Scripta Minoa I: The Hieroglyphic and Primitive Linear Classes. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Evans, A. J. (1901–1902). “The Palace of Knossos: Provisional report of the Excavations for the Year 1902.” BSA 8: 1–124.

Steele, P. M. and Meißner, T. (2017). “From Linear B to Linear A: The Problem of the Backward Projection of Sound Values.” In Understanding Relations Between Scripts: The Aegean Writing Systems, edited by P. M. Steele, 93–110. Oxford–Philadelphia: Oxbow.

Salgarella, E. and Petrakis, V., eds. (2025). The Wor(l)ds of Linear A: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Documents and Inscriptions of a Cretan Bronze Age Script. AURA Supplement 15. Athens: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Salgarella, E. (2025). Writing in Bronze Age Crete: ‘Minoan’ Linear A. Cambridge Elements in Writing in the Ancient World Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, B. (2014). Minoan Stone Vessels with Linear A Inscriptions. Aegaeum 36. Leuven: Peeters.

Davis, B. (2013). “Syntax in Linear A: The Word-Order of the ‘Libation Formula.’” Kadmos 52: 35–52.

Schoep, I. (2002). The Administration of Neopalatial Crete. A Critical Assessment of the Linear A Tablets and their Role in the Administrative Process. Suplementos a Minos 17. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

Del Freo, M. and Zurbach, J. (2024). Recueil des Inscriptions en Linéaire A. Supplément 1. ÉtCrét 21:6. Athens: École Française d’Athènes.

Packard, D. W. (1974). Minoan Linear A. Berkeley: University of California Press.

“Minoan drinking cup: something clay, something old, something new.” Things That Talk. https://thingsthattalk.net/en/t/ttt:TQfYGq/details

Ferrara, S. and Weingarten, J. (2022). "Cretan Hieroglyphic Seals and Script: A View from the East." Pasiphae 16, 111–121.

Ferrara, S., & Cristiani, D. (2016). Il geroglifico cretese: Nuovi metodi di lettura (con una nuova proposta di interpretazione del segno 044). Kadmos, 55(1–2), 17–36.

Inquiries from researchers, experimentalists, and potential collaborators are welcome. Contact Symfield

© 2026 Symfield PBC. All rights reserved. Priority established via blockchain timestamp Feb 9, 2026.

This work may not be reproduced, adapted, or used to derive experimental protocols without written permission from the author.